Introduction

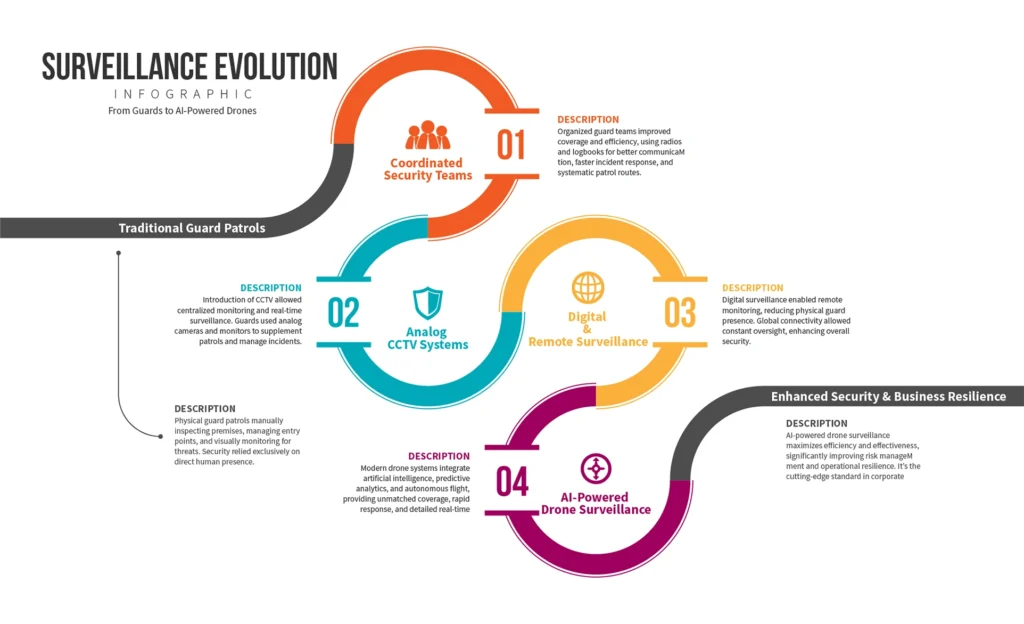

In an era defined by rapid technological advancement, drone technology has dramatically transformed corporate security capabilities. Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) – commonly known as drones – now serve as agile “eyes in the sky,” providing surveillance coverage and response capabilities that were unimaginable with traditional guards and fixed cameras. Unlike static CCTV cameras or patrol routes limited by human endurance, drones can autonomously roam across vast facilities, zoom in on details from hundreds of feet above, and relay real-time video to security teams. This evolution marks a paradigm shift: organizations are moving from reactive security postures to proactive, technology-driven strategies. For instance, businesses that blended drones with conventional measures have seen up to a 30–40% reduction in security incidents and 60% cost savings compared to guard-only programs (Drone Industry Visionary Interview: Ryan Smith defines the tangible (and invisible) ROI of drone security | Commercial UAV News). Such results underscore how aerial surveillance isn’t just a novel gadget – it’s a force multiplier for corporate security.

Traditional security methods – locked doors, alarm systems, guard patrols, and CCTV networks – will always have their place. However, they also have inherent limitations. Fixed cameras cover only their line of sight, leaving blind spots; guards on foot or in vehicles can be in only one place at a time and may take precious minutes to respond to far-flung incidents. By contrast, drone surveillance offers unmatched agility and reach. A single drone can patrol an area that would otherwise require multiple cameras or roving guards, eliminating blind spots and reducing response time to mere seconds (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). Modern security drones come equipped with high-definition day/night cameras and thermal imaging, acting as ever-vigilant sentinels that can detect movement in dark or hard-to-access areas. They provide a bird’s-eye view of assets and perimeters, which is invaluable for monitoring large campuses, industrial sites, and events (Navigating Modern Security Challenges: The Crucial Role of Physical and Surveillance Security Solutions – Cuneo Consulting). In effect, drones extend the perimeter of awareness far beyond the fences – they are the unblinking eyes that can continuously watch over corporate interests from above.

Equally important is how drone surveillance enables a proactive security posture. Rather than waiting for an alarm to sound or a breach to be discovered after the fact, drones can conduct regular patrols and respond instantaneously to triggers. For example, if an intrusion sensor trips at a remote corner of a facility at 2 AM, a drone can be dispatched immediately to investigate, potentially spotlighting an intruder within moments – long before a guard could ever arrive. This rapid verification not only helps intercept threats in progress, but also drastically cuts down on false alarms (since the drone’s feed can confirm whether an intrusion is real or just a stray animal). By contrast with traditional methods, which often involve after-the-fact review of camera footage or laborious guard tours, drones facilitate real-time, intelligence-driven security. They act as a deterrent (an intruder who sees a drone overhead is likely to flee) and as a frontline response tool that guides ground teams more effectively. In short, a modern corporate security strategy that integrates drones is far more dynamic and preventive than one relying solely on static measures.

It’s no surprise, then, that corporate adoption of security drones is accelerating. The global surveillance drone market is booming – projected to reach around $5.5 billion in 2023 with annual growth over 14% going forward (Surveillance Drone Market Size & Share | Growth By 2034 – Fact.MR). What was once bleeding-edge technology restricted to military or government use is now an accessible business tool. From Fortune 500 corporate campuses to mid-sized industrial parks, organizations are embracing drones to protect assets and people. Early adopters have demonstrated clear returns on investment (ROI) and competitive advantages: better loss prevention, improved safety, and often lower operational costs. Executives are taking note that drone surveillance is not just a security expense, but a strategic investment. It yields tangible benefits like reduced theft and vandalism, improved incident response, and enhanced situational awareness for management. As a result, drone overflights of corporate rooftops and perimeters are increasingly as routine as morning badge swipes at the front door.

This comprehensive article serves as a definitive resource on “Drone Surveillance for Corporate Security.” It will guide you through every aspect of adopting and leveraging drones as part of a modern security program – from the high-level strategic rationale down to the technical nuts-and-bolts and regulatory checkpoints. We begin by examining the strategic and operational imperatives driving drone deployment in corporate security, including ROI analyses and executive-level benefits. Then, we dive deep into drone technology – exploring platform types, sensors (payloads), performance metrics, and maintenance considerations that Security Directors must understand. We’ll explore core applications and sector-specific use cases, illustrating how drones are applied in industries ranging from logistics and critical infrastructure to corporate campuses and retail. Next, we discuss strategies for seamless integration of drones into your existing security ecosystem – ensuring your aerial assets work in tandem with video management systems, access control, and alarm monitoring. We also tackle the vital topics of regulatory compliance and ethics – navigating FAA rules, privacy concerns, and insurance requirements to deploy drones lawfully and responsibly. For those ready to implement, we provide a step-by-step blueprint for developing a corporate drone program, covering everything from pilot training to standard operating procedures (SOPs) and performance monitoring. Finally, we cast an eye to the future in emerging trends, such as AI-driven autonomy, drone swarms, and counter-drone defenses, so you can future-proof your security strategy.

By the end of this guide, C-suite executives, Security Directors, Compliance Officers, and Operations Managers will have a 360-degree understanding of how to integrate drone surveillance into corporate security – and why doing so is fast becoming indispensable for advanced protection. Drone surveillance is more than a buzzword; it’s a game-changing component of proactive security that can safeguard your organization in ways previously unattainable. The “unblinking eye” of a drone never tires, never blinks, and never looks the wrong way – providing continuous vigilance over what matters most.

The Strategic & Operational Imperative for Drone Surveillance

Why have drones so quickly moved from novelty gadgets to must-have corporate security tools? This section explores the strategic and operational drivers behind the imperative to adopt drone surveillance today. In a climate of evolving threats, cost pressures, and technological opportunities, drones offer a compelling value proposition. We will examine the business case – including return on investment (ROI) and total cost of ownership (TCO) – and compare drone-based security to traditional methods like staffed patrols and static cameras. The goal is to articulate why investing in drone surveillance makes sense at the executive level, and how it can yield dividends in security effectiveness and efficiency.

Evolving Threats Demand Proactive Surveillance

Modern enterprises face a more complex threat landscape than ever. Corporate campuses, distribution centers, and industrial facilities must contend with risks ranging from organized theft rings and espionage to vandalism and workplace violence. Traditional security measures alone (fences, alarms, guards) are often insufficient to deter or respond to these advanced threats. Drones fill critical gaps by providing rapid, flexible coverage. Aerial surveillance is essentially omnipresent and omnidirectional – drones can see over and around obstacles, giving security teams insight into areas that adversaries might exploit. For example, during the 2023 Boston Marathon (a high-threat public event), authorities employed drone surveillance to cover zones that ground police could not easily see, helping ensure an incident-free environment (Navigating Modern Security Challenges: The Crucial Role of Physical and Surveillance Security Solutions – Cuneo Consulting). This kind of capability is directly transferable to corporate settings: a drone can watch a perimeter fence line or a parking lot from above, detecting intruders or suspicious vehicles that would escape notice from the ground.

Moreover, the mere presence of visible security drones can alter the behavior of potential wrongdoers. Much like the deterrence effect of security cameras (often cited as reducing theft by significant percentages), drones up the ante – they are mobile, unpredictable, and can follow an intruder in a way a fixed camera cannot. Would-be trespassers or thieves recognize that once a drone locks onto them, hiding or escaping becomes far more difficult. This psychological deterrent is a new arrow in the corporate security quiver, contributing to a more hardened target. In essence, drones raise the cost and risk for adversaries, thereby lowering the likelihood of security incidents.

Demonstrable ROI for Businesses of All Sizes

Cost is a constant concern in corporate security management. Executives need to justify expenditures by showing improvements to the bottom line, either through loss prevention or operational savings. Here, drone surveillance makes a powerful financial case. While drones do require upfront investment and ongoing maintenance, they often enable significant cost efficiencies when compared to traditional methods. Consider the labor costs of manned security: a single full-time security officer (with salary, benefits, training) can cost $50,000–$70,000 per year or more. Yet one officer can patrol only a limited area. To secure a large facility 24/7, many officers are needed, driving personnel costs into the hundreds of thousands. Cameras are cheaper long-term but have high installation costs per location and still require personnel to monitor. Drones, by contrast, can reduce the need for multiple guards and cameras by covering their duties with one device. After an initial purchase or lease, a drone’s operating cost is mainly electricity and periodic maintenance – minimal compared to a human salary.

Real-world examples underscore this ROI. Titan Protection, a U.S. security firm, pioneered a “blended” approach using drones to augment its guard services. The result was a 60% reduction in security labor costs for clients and a simultaneous drop in incidents by 30–40% (Drone Industry Visionary Interview: Ryan Smith defines the tangible (and invisible) ROI of drone security | Commercial UAV News). In other words, drones made security not only more effective but also more economical. Many companies are discovering similar economics. In one industry survey, 92% of companies using drones reported seeing ROI within one year of deployment (Security Drones: Benefits, Use Cases and ROI of Using Drones in the Security Industry). Savings come from multiple avenues: reduced theft losses (thanks to better deterrence and quick response), lower headcount or overtime for security staff, fewer false alarms and associated disruption, and possibly even lower insurance premiums. For instance, a manufacturing company that suffered frequent after-hours break-ins might invest in a drone patrol program. If theft losses drop by $200,000 in the first year (due to intruders being scared off or caught by drones) while program costs are $100,000, that’s a clear net positive ROI – and improved safety to boot.

ROI analysis should also consider avoided costs. A single major security breach – such as a theft of valuable intellectual property or a safety incident due to an undetected intruder – can cost millions in damage, legal claims, and reputational harm. Drones act as an insurance policy against such catastrophic events. It’s hard to measure the exact dollar value of an incident that didn’t happen because a drone was watching, but preventing one serious incident can itself justify the investment many times over.

From small businesses to large enterprises, the scalability of drone programs means the model can fit various budgets. A small business (say a regional warehouse or a data center) might start with one affordable drone and a part-time pilot, focusing on the highest-risk times (night and weekends). Even this limited use can yield outsized benefits by catching that one critical incident or providing valuable situational awareness during an emergency. Mid-sized companies could opt for a fleet of drones on rotational patrol, significantly extending their security reach without multiplying staff. Global corporations are beginning to implement enterprise drone programs across multiple sites, coordinated through a central command center – a concept that promises economy of scale and standardized protection. The key is that drones are modular and flexible: you can deploy as few or as many as needed, and add more units as your operations grow or risks change.

Drone Surveillance TCO Calculator

Traditional Security Costs

Drone Surveillance Program Costs

TCO Comparison Results

Traditional Security Costs

Drone Program Costs

Return on Investment

Total Cost of Ownership Considerations

While ROI highlights the benefits, decision-makers must also weigh the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) for drone surveillance. TCO includes not just the purchase price of drones, but all ongoing costs: maintenance, battery replacements, software subscriptions, pilot training, regulatory compliance efforts, insurance, etc. Fortunately, drones tend to have favorable TCO profiles when planned carefully. Quality commercial-grade security drones can range from $5,000 to $50,000 each depending on capabilities. Additional equipment might include spare batteries, charging stations, controller devices, perhaps a drone “dock” or hangar if using automated launch systems. On the operational side, you need licensed pilots (which could be existing security staff cross-trained, or external service providers), and those pilots will need periodic refresher training and certification renewal. Maintenance involves routine checks, firmware updates, part replacements (propellers, motors) and occasional repairs.

When spread over the lifespan of the equipment (typically 3–5 years for intensive use, though many drone airframes can last longer with upgrades), these costs often come out lower than equivalent human patrol costs over the same period. For example, the annual maintenance and support cost for a drone might be a few thousand dollars – trivial next to a full-time guard’s yearly wages. One analysis by a security integrator found that once deployed, a single drone can effectively cover areas that would require 3–4 security guards or dozens of CCTV cameras, but at a fraction of the ongoing cost (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). The cost to scale up is also low – adding a new drone to cover expanded operations doesn’t require constructing new guard posts or extensive infrastructure; it’s a matter of purchasing another unit and integrating it. As a result, drones offer near-linear scalability: doubling your coverage with drones might roughly double your costs (plus modest training additions), whereas doubling coverage with guards could more than double costs when you factor in management, shift overlaps, etc. (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). This scalability is extremely attractive for growing businesses or those with fluctuating security needs (for instance, a company that needs extra surveillance only during certain high-risk projects or seasons can deploy more drones temporarily).

TCO calculations should include software and data costs as well. Many drone systems require subscriptions to management software or data storage for recorded footage. However, these software platforms often bring powerful features like automated flight planning, AI analytics, and cloud backup that significantly enhance the value of the drones. Executives evaluating TCO should ask vendors about package deals or enterprise licensing that can cover multiple drones under one plan. Additionally, working with an experienced security consultant can help in planning a cost-effective deployment – avoiding common pitfalls that lead to hidden costs. For instance, buying consumer-grade drones might save money upfront but could lead to higher failure rates and replacements (a classic false economy). Investing in enterprise-grade drones and robust integration yields better long-term reliability – an important TCO consideration.

In summary, when viewed over a multi-year horizon, the TCO of a well-implemented drone surveillance program is highly competitive. The combination of reduced labor expenses, scalable expansion, and prevention of costly incidents contributes to a compelling business case. Companies should perform a detailed cost-benefit analysis, but in many scenarios the numbers favor drones, especially when intangible benefits (like improved safety culture and stakeholder confidence) are factored in.

Drones vs. Traditional Security Methods

To fully appreciate the strategic imperative of drone surveillance, it’s helpful to directly compare drones with the traditional security methods they augment or replace: namely, human guards and fixed surveillance cameras. Each approach has strengths; the goal is to understand where drones excel and how they can fill the gaps of conventional measures.

- Coverage and Visibility: Traditional cameras are stationary – they provide a continuous watch but only in a fixed field of view. Guards can move, but their vantage point is limited to ground level. Drones combine the best of both: continuous surveillance with mobility. A single drone at 200 feet altitude can surveil an area that would require many static cameras to cover, and it can reposition on demand to track movement or eliminate blind spots (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). Unlike a guard who might have to walk around a building to see behind it, a drone can simply fly over in seconds. In effect, drones blanket your facility with an on-demand aerial mesh of visibility, greatly reducing blind areas. Traditional methods struggle with complex terrain (hills, dense equipment yards, etc.), whereas drones literally rise above the challenge.

- Responsiveness: When an incident occurs, time is critical. A guard might take several minutes or more to reach a far corner of a property after an alarm. Police response times can be even longer. Cameras can record events, but they don’t move to follow a suspect – someone watching the feed must direct ground responders. Drones excel in speed of response. The moment an alarm triggers or suspicious activity is detected, a drone can be autonomously dispatched to that exact location, often arriving in under a minute – long before a person could. For example, if a fence sensor detects a breach, a drone can zip over and start streaming video of that spot, giving security a real-time assessment (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). This rapid response can mean the difference between scaring off or catching an intruder versus arriving to find them long gone. In safety scenarios (say, a fire or chemical spill), drones can provide eyes on the scene far faster than any human, helping first responders with critical information. Traditional guards simply cannot match the reactive agility of drones.

- Endurance and Reliability: Human guards have limitations – they can become fatigued, distracted, or simply have a bad day. They also require breaks, shift changes, and management oversight. Cameras don’t fatigue, but their effectiveness can wane in bad weather or poor lighting unless they’re high-end models, and even then they might need auxiliary lighting. Drones can operate programmed patrols tirelessly and—when equipped appropriately—can see in darkness (thermal imaging) and aren’t impeded by most weather aside from extremes. While a drone’s battery life is finite (typically 20–40 minutes for many models), this is mitigated by using multiple drones in rotation or tethered drones for constant power. In essence, drones offer reliable, repeatable performance for routine surveillance tasks. They will never “nod off” during a dull midnight shift. With AI automation, they can also notify human operators only when something truly requires attention, increasing overall reliability of detection. Of course, drones do require human involvement for decision-making and maintenance, but they significantly reduce the mundane workload on security personnel, freeing staff to focus on analysis and action rather than walking endless rounds or staring at banks of monitors.

- Adaptability and Scalability: Security needs can change rapidly – perhaps a particular asset becomes high-value overnight, or a new construction project creates a temporary vulnerability. Traditional security is often slow to adapt (hiring new guards or installing new cameras takes time and money). Drones are extremely adaptable. Need extra eyes on the loading dock this week? Assign the drone more frequent passes there. Expansion of the facility? Simply extend the drone’s patrol route or add another drone to cover the new area. During special events (shareholder meeting, product launch party, etc.), drones can be deployed specifically for the duration of the event and then re-tasked elsewhere afterward. This flexible scaling is a strategic asset. According to security experts, adding more drones to a fleet is straightforward and doesn’t significantly disrupt existing infrastructure, whereas scaling guards or cameras involves substantial overhead (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods) (Cost-Effective Security: Comparing Drone Security to Traditional Methods). Executives appreciate that drone programs can grow with the business or be reconfigured as threats evolve, protecting the investment over the long term.

- Capabilities: There are tasks simply beyond the capabilities of traditional methods. For example, thermal imaging from an aerial viewpoint can detect a hidden trespasser at night far more effectively than a flashlight-wielding guard or a night-vision CCTV. Drones can also be equipped with loudspeakers to issue warnings, something a camera certainly can’t do. In some cases, a drone might even be able to intervene (non-lethally) by sounding an alarm or spotlighting an intruder to disorient them. While guards have the advantage of physical intervention (drones can’t handcuff a suspect – at least not yet!), they often must find the suspect first, and that’s where drones tilt the scales. The ideal approach is blending the two: drones find, track, and illuminate the threat, while ground personnel intercept and apprehend – a symbiosis that vastly improves safety for the guards, who have much more information about what they’re walking into.

Of course, traditional methods still have their place. A drone won’t replace the reassurance of a friendly security officer greeting employees, nor can it perform tasks like badge checks or physically lock a door. Instead, drones enhance and focus human effectiveness. By taking over the monotonous patrols and the initial recon of any alarm, drones free up human guards to concentrate on tasks that require judgment, customer service, and physical intervention. The comparison isn’t drones or humans – it’s the optimal combination of drones, humans, and static systems to achieve the highest security level for the lowest cost.

From a strategic viewpoint, organizations that leverage drones are effectively arming their security teams with a powerful new tool that competitors or adversaries may lack. It’s akin to moving from horse-mounted watchmen to CCTV in the mid-20th century – those who adopted CCTV early gained a security edge. Today, drones are that edge, offering capabilities that set apart a cutting-edge corporate security program from a conventional one. In boardroom terms, deploying drones aligns with a forward-leaning risk management strategy and demonstrates innovation in protecting the company’s assets and people.

Executive-Level Benefits and Risk Mitigation

For C-suite executives and enterprise risk managers, drone surveillance offers benefits that resonate beyond the security department. One major advantage is holistic risk mitigation. Drones can reduce not only security risk (like theft or sabotage) but also safety and operational risks. They can quickly inspect facilities after natural disasters or accidents (identifying hazards before people enter), and they can monitor compliance (for example, checking that safety protocols are followed in remote yard areas). This contributes to business continuity and resiliency, protecting the company’s operations from disruptions. Seen in this light, the investment in drones is an investment in keeping the business running smoothly under adverse conditions – a clear executive concern.

Another benefit at the executive level is data and intelligence. Drones don’t just provide security; they collect valuable data that can be analyzed for insights. Patterns observed in drone surveillance might reveal, say, a recurring bottleneck in a facility’s traffic flow or an employee behavior that raises safety issues. Over time, drone footage and sensor readings can be mined (with the help of analytics software) to inform decisions outside of security – like facility planning or process improvements. In essence, a network of security drones doubles as a data acquisition tool for the enterprise, aligning with trends in big data and IoT (Internet of Things). A forward-thinking executive can leverage this for cross-departmental value.

From a governance and compliance perspective, deploying state-of-the-art security like drones also shows regulators, insurers, and investors that the company takes asset protection seriously. In some industries, having advanced surveillance might help demonstrate compliance with security requirements or industry standards (for instance, critical infrastructure sectors often have stringent surveillance mandates – drones can help meet them). There’s also an argument to be made that proactive drone use can reduce liability. If an incident does occur, the company can show it had robust measures in place; and drone footage can provide clear evidence of what happened, which might limit legal exposure. Many legal and insurance stakeholders increasingly see drones as part of best practices for facility security.

At the brand and reputational level, being known as an organization that employs cutting-edge security tech can bolster an image of innovation and safety. Clients, visitors, and employees may feel more secure knowing that the premises are monitored by advanced drones as well as guards. It sends a message: this company is serious about protection. Of course, messaging must be balanced with privacy (more on that in the compliance section), but generally, a well-communicated drone program can reassure stakeholders that the environment is under vigilant control. This is especially important for companies that invite clients on-site (like data centers showing their secure measures to customers, or manufacturers hosting auditors). A quick anecdote can illustrate: A large corporate campus in California implemented routine drone patrols and publicized it internally – within months, employee surveys noted improved feelings of safety on campus, as employees knew that if they worked late, a drone was circling the parking lots to watch over them. Happier, safer employees are certainly an executive-level benefit, contributing to talent retention and productivity.

In sum, the strategic imperative for drone surveillance in corporate security is clear. We have a confluence of factors – evolving threats, proven ROI, manageable TCO, superior capabilities, and broad organizational benefits – that make a compelling case. Forward-looking executives and security leaders recognize that continuing to rely solely on yesterday’s methods is a liability. Embracing drone technology is a way to future-proof the security strategy, gaining both quantitative and qualitative advantages. As we move to the next sections, keep in mind how these high-level motivations set the stage for the practical implementation: understanding the technology itself, applying it effectively, and integrating it seamlessly. The business case is the “why,” and it’s robust; next we delve into the “what and how” of drone systems that deliver on this promise.

Drone Technology Deep-Dive: Platforms, Payloads, and Performance

To successfully integrate drones into corporate security, one must understand the technology at a fundamental level. This section provides a deep dive into the nuts and bolts of security drone systems – the platforms (types of drones) available, the payloads (sensors and equipment) they carry, and key performance factors that determine what a given drone can do. We’ll compare different drone types (from nimble quadcopters to long-endurance fixed-wing models), explore the range of surveillance tools (cameras, thermal imagers, etc.) they can deploy, and discuss the practical aspects of keeping drones running reliably (maintenance, battery life, weather considerations). By the end of this section, Security Directors and technical managers will have a solid grasp of how to select the right drones for their needs and what operational trade-offs to expect.

Drone Platform Types: Finding the Right Fit

Not all drones are created equal – various platform designs exist, each with strengths tailored to particular use cases. The main platform categories to consider for corporate security are multirotor drones, fixed-wing drones, and hybrid VTOL drones. Understanding their differences is crucial in matching the tool to the task.

- Multirotor Drones (Quadcopters and more): The most common security drones are multirotors – often quadcopters (4 rotors) but also hexcopters or octocopters for heavier lift. These drones take off and land vertically, hover in place, and maneuver with precision. Key advantages: They excel at stationary observation and slow, deliberate movement. This makes them ideal for tasks like perimeter patrol (flying low and following a fence line) or zooming in to inspect a specific spot (a door left open or an unidentified object). They are generally easy to deploy and control, even in tight spaces, and can take off from a small patch of ground or a rooftop. Many security-focused drones on the market – such as the DJI Matrice series or the Autel Evo series – are multirotors. Modern multirotors typically offer flight times in the range of 20–40 minutes per battery, speeds up to 30–50 mph, and can carry moderate payloads (a high-resolution camera plus perhaps a loudspeaker or spotlight). Limitations: Their relatively short flight endurance means they either need frequent battery swaps or a rotation of units to maintain continuous coverage. They also have lower aerodynamic efficiency, so they’re not ideal for very long distance patrols (beyond, say, a couple of miles of total travel per flight). However, for most corporate campuses and facilities, multirotors provide ample coverage. Their ability to hover means they can also serve as “virtual tower cameras” – holding a high vantage point over an area of interest for extended periods (until the battery runs out). If constant overwatch is needed at a fixed spot, some companies use tethered multirotors – drones attached via a cable to a ground power source, allowing 24/7 flight (at the cost of being confined to the tether’s length radius). In summary, multirotors are versatile and user-friendly, suitable for the majority of security scenarios requiring up-close observation and agile response.

- Fixed-Wing Drones: These drones resemble small airplanes with wings. They need to move forward to generate lift (like a plane) and cannot hover in place. Key advantages: Fixed-wing drones have significantly longer flight times – often 1–2 hours or more on a battery or fuel cell, and they can cover great distances fast. This makes them valuable for extremely large properties or linear infrastructure. For example, a pipeline company or a sprawling industrial site (such as a 10,000-acre solar farm) might use a fixed-wing drone to routinely fly long surveillance routes. Fixed-wings are also more stable in strong winds and can reach higher altitudes and speeds (some can cruise at 60–100 mph). Limitations: They usually require either a runway/takeoff strip, a catapult launcher, or a parachute recovery system – which isn’t practical in many corporate environments. Some smaller fixed-wing drones can be hand-launched, but landing them without damage can be tricky without a runway or net. Crucially, since they can’t hover, fixed-wings are not suited to loiter over a spot or navigate within tight confines (e.g., around buildings or courtyards). Their surveillance style is more like a constant broad sweep. Imagine a fixed-wing doing continuous loops around a facility’s perimeter – great for general oversight, but if an incident is detected, a multirotor might still be needed to hover and closely monitor the situation. Fixed-wings also often carry lighter payloads (due to the need to stay aerodynamic). They might have a camera but usually less payload flexibility than a multirotor. In corporate security, fixed-wing drones are somewhat niche – used when very large area coverage and endurance are top priority, and usually in rural or expansive campus settings where launch/landing is manageable.

- Hybrid VTOL (Vertical Takeoff and Landing) Drones: Bridging the gap between the above types, hybrid VTOL drones have the features of both multirotors and fixed-wings. They might have rotors that tilt or separate lift and thrust systems – allowing them to take off vertically like a helicopter, then transition to winged flight for efficient cruising. Key advantages: VTOL hybrids offer hover capability along with extended range. This can be a game-changer for certain applications – for instance, a security drone that can launch from a parking lot, fly 10 miles of fence line, then stop and hover to zoom in on a detected anomaly. Several emerging security drone platforms use VTOL designs to enable autonomous coverage of large perimeters without the infrastructure of runways. Flight time on hybrids typically falls between multirotors and fixed-wings (perhaps 45–60 minutes), and their payload capacity can be moderate. Limitations: They are more mechanically complex, potentially meaning higher cost and maintenance. Also, some hybrids sacrifice a bit of efficiency for the VTOL convenience, so they might not match pure fixed-wing endurance or pure multirotor agility perfectly; they’re a compromise. That said, for many corporate security operations, a VTOL drone presents an attractive all-in-one solution: sufficient endurance to patrol large sites and the ability to hover for detailed inspection. As drone technology advances, more refined VTOL security drones are hitting the market, and they are worth considering for forward-looking programs that need both coverage and station-keeping ability.

In addition to these categories, there are specialized platforms like drone-in-a-box systems. These aren’t a different airframe type per se (they are usually multirotor or VTOL drones), but they are sold as an integrated package that includes a sheltered charging station. The drone can land in its “box” which then charges it and protects it from weather, enabling fully automated 24/7 operation. For example, a warehouse might place a drone-in-a-box at the facility’s roof; the drone can auto-launch on a schedule or when triggered by an alarm, then return to recharge – all without human handling. These systems are increasingly popular for corporate security because they minimize the need for on-site drone pilots for routine patrols. The box often has climate control to extend battery life and health. Companies like Percepto and Azur Drones offer such solutions, and even some mainstream drone makers are adding docking stations to their lineup. While these systems involve a higher upfront cost, they effectively turn drones into autonomous security guards that can respond day or night, which might be invaluable for high-security or remote sites.

When selecting a platform, security managers should consider the layout and size of the area to secure, the typical mission profiles (persistent overwatch vs. quick response vs. long patrols), and the available infrastructure for drone operations. Often, the answer might be a mix: multirotors for rapid response and detailed inspection, and perhaps a fixed-wing or hybrid for long-haul surveillance or backup. Compatibility and integration across platforms are also a factor – it may be convenient to stick with a single vendor ecosystem for ease of training and maintenance.

Payloads and Sensors: The Drone’s Toolkit

A drone is only as useful as the sensors and tools it carries. In corporate security applications, the payload – typically a suite of cameras and other sensors – is what allows the drone to detect, recognize, and sometimes deter threats. Here we explore the most common and valuable payload types for security drones:

- High-Definition Cameras (Electro-Optical Day Cameras): The staple of drone surveillance is a stabilized HD camera that provides live video feed and recordings in the visible light spectrum. Modern security drones often feature 4K resolution cameras with high zoom capabilities (20× optical zoom or more is common). This allows operators to get clear details – for example, reading a license plate or identifying a person’s clothing – from a safe height. Many cameras are mounted on a gimbal, giving 360-degree rotation and tilt, so the drone can look in any direction without needing to reposition the whole aircraft. This is crucial for tracking moving targets or scanning wide areas. Some drones even have multiple optical cameras for wide-angle overview and zoomed-in detail simultaneously. In daytime and well-lit conditions, HD cameras are the primary eyes of the drone, capturing color video evidence. They are also useful for documentation (like recording an intruder’s actions for later prosecution, or surveying damage after an incident).

- Thermal Infrared Cameras: Thermal imagers detect heat signatures and form an image based on temperature differences. This is incredibly useful for night surveillance or any low-light environment – where traditional cameras might struggle or require flood lights, thermal cameras can spot humans or vehicles by their heat alone. For security use, thermal payloads allow detection of people hiding in bushes or shadowy areas, and can even help in smoke or fog where visibility is otherwise poor. Many security breaches happen at night, and a person’s body heat is a giveaway even if they wear dark clothing and avoid visible light. Drones equipped with dual optical/thermal cameras give operators a fused view: the thermal image highlights warm bodies, while the optical can often provide identifying details if some light is present. Thermal cameras come in various resolutions (common ones are 320×240 or 640×480 pixel sensors, which are much lower than visual cameras but sufficient to detect humans). When shopping for a security drone, a dual-sensor gimbal (optical + thermal) is highly recommended for 24/7 capability. It effectively turns night into day for the security team. As a bonus, thermal drones can also detect heat anomalies on equipment (like an overheating transformer or a smoldering fire) as part of safety monitoring.

- Low-Light/IR-Enhanced Cameras: Between normal daytime cameras and full thermal, there are cameras specifically designed for low-light conditions. These might include starlight sensors that can capture color video in very dim conditions, or cameras that switch to a black-and-white high sensitivity mode at night. Some drones carry an infrared illuminator (essentially an IR flashlight) and an IR-sensitive camera; this combination works like night vision, illuminating the area with infrared light invisible to the naked eye but allowing the camera to see clearly. This is useful if you want to identify someone at night without using a visible spotlight that tips them off – the drone can quietly light them up in IR and see details. Low-light cameras are not as universally effective as thermal for detection, but they provide clearer facial or object details in darkness when close enough, complementing thermal detection.

- LiDAR and 3D Mapping Sensors: Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) sensors use lasers to create precise 3D maps of the environment. In security, LiDAR is less common than optical/thermal cameras, but it has niche uses. One use is intrusion detection: a drone equipped with LiDAR could scan an area and detect changes or moving objects with great accuracy, even distinguishing something small like a crawling intruder in tall grass. LiDAR can also help navigate in GPS-denied environments, although that’s more relevant for autonomy than surveillance. Some high-end security drones might incorporate a LiDAR to map the facility’s layout – useful for creating digital twins of your site or for coordinating autonomous patrol routes with obstacle avoidance. While not a must-have for every program, LiDAR is an example of how drones can carry advanced sensors that turn them into flying inspection tools, beyond just cameras.

- Acoustic Sensors: A newer frontier is putting microphones or acoustic triangulation sensors on drones, to detect gunshots or unusual noises. For instance, a drone could be equipped with a gunshot detection system that alerts when a firearm is discharged, flying immediately to the source. Acoustic sensors on drones face challenges (propeller noise, wind noise), but research is ongoing. Some security scenarios, such as campus security, might benefit from a drone that can “hear” alarms or distress shouts in addition to seeing.

- Deterrence and Response Payloads: Drones can do more than watch – they can act. A range of deterrent payloads are available:

- Spotlights: A high-powered LED spotlight can be mounted to light up suspects on the ground. This has a psychological effect (suddenly being in a drone’s spotlight can freeze a trespasser) and aids video capture. It also helps any responding guards by illuminating the area.

- Loudspeakers: Drones can carry a speaker to broadcast messages or siren sounds. An operator could remotely shout a warning like, “You in the black jacket, you are trespassing – security is en route,” which might prompt an intruder to flee immediately. Loudspeakers are also useful in emergency scenarios to relay instructions to people over a wide area (e.g., in an evacuation, a drone could guide people out).

- Sirens/Strobes: Some drones have built-in loud sirens or flashing strobe lights purely to startle and draw attention. These can be triggered to let an intruder know they’ve been detected and to alert any nearby personnel.

- Delivery Mechanisms: In specialized cases, drones might carry small payload drop systems or attachments (for example, a drone could drop a smoke canister or a GPS tracker onto a vehicle). In corporate security, lethal or harmful devices are not used (weaponizing drones is heavily regulated and generally not ethical or legal for private use). But benign payloads could be used – like dropping a life jacket to a person in water (a lifesaving use rather than security, but worth noting how versatile drones can be). Some security drones also carry non-lethal defense mechanisms; one Israeli firm developed a drone that can deploy pepper spray or tear gas for riot control – however, such uses would require extreme caution and likely law enforcement partnership.

- “Net Guns” or Counter-intruder tech: On the horizon are drones that can intercept other drones (in case an adversary uses a drone against your facility). These often use net launchers. This falls more under counter-drone than routine security, but it’s notable that drones can both be a surveillance asset and also be configured to counter airborne threats if needed (see Future section for more on counter-drone).

When choosing payloads, consider the primary objectives of your drone operations. For most corporate security programs, a combination of a high-resolution day camera and a thermal night camera (often in one gimbal unit) is the baseline. This ensures 24-hour detection and recognition capability. Add a spotlight and loudspeaker if deterrence is part of your plan to intervene on incidents in progress. Ensure the drone’s gimbal can stabilize the camera in wind and during drone motion – clarity of footage is paramount for identifying suspects or situations.

It’s also important to note payload weight and power impact performance. A drone carrying a heavy camera and spotlight will have shorter flight times than one carrying just a small camera. Always check the drone’s specifications for how different payload configurations affect endurance and handling. Many enterprise drones advertise flight time “up to X minutes” which might be with no payload; in real security use with dual cameras and accessories, the flight time could be somewhat less. Plan conservatively in that regard.

From a maintenance perspective, payloads may need their own upkeep – camera lenses cleaned, firmware updated, calibrations done for sensors like thermal imagers. Security managers should include the payload in their maintenance checklists (for example, ensure the thermal camera is properly calibrated for temperature readings if being used to detect equipment overheating, etc.).

Finally, consider future expansion: you might not need LiDAR or advanced sensors now, but choosing a drone platform that supports payload swapping or upgrades can be wise. Some drone systems are modular – you can attach different payloads as needed. This means you could, for instance, use a high-zoom camera during normal operations, but swap in a specialized hazmat detection sensor (yes, those exist – like sniffers for chemical leaks) during a specific incident. While swapping payloads often requires landing and some manual work, the flexibility can greatly increase the drone’s utility across various scenarios, providing a better return on the investment.

Performance Factors: Flight Time, Range, and Weather Resilience

When deploying drones for security, understanding their performance envelope is critical to planning operations. Key performance factors include flight time (endurance), range, speed, maneuverability, and environmental resilience. Here’s what security teams need to know about each:

- Flight Time (Endurance): This is the duration a drone can stay airborne on a single battery charge or tank of fuel. As noted, multirotors generally have shorter flight times (20–40 minutes) while fixed-wings and hybrids can go longer (60+ minutes). Endurance directly affects how you schedule drone patrols. For example, if you need to surveil a perimeter continuously overnight, a single multirotor won’t suffice – you’d need multiple drones cycling in and out of a charging station, or a tethered solution. Many corporate security operations find that having at least two or three batteries per drone is essential: one in use, one charging, one cooled down ready to swap (since batteries heat up and often need to cool before recharging). Advanced drone-in-a-box systems mitigate this by automated battery swapping or charging. It’s also worth noting that real-world flight time can differ from spec sheets: flying in wind, carrying heavier payloads, or lots of aggressive maneuvering will drain batteries faster. Cold weather can also reduce battery efficiency. Security managers should conduct their own tests under typical conditions to know the reliable flight time. As a rule, plan missions to use only ~80% of a battery to leave a safety margin for return-to-base. If a drone has 30-minute average endurance, plan ~20–24 minute patrols then return to swap. Fortunately, battery technology is improving incrementally year by year, and options like hydrogen fuel cells are emerging for longer electric flight. Some security drones advertise swappable battery packs that can be changed in under 2 minutes, minimizing downtime. Endurance is a crucial performance metric because it dictates coverage: a drone with longer flight time can simply do more on each sortie, reducing the number of drones or sorties needed.

- Range and Communication: Range has two aspects – how far the drone can physically fly (which is limited by battery and airspace regulations) and how far the control/data link can operate. FAA regulations (in the US) currently require drones to be within the pilot’s visual line of sight (VLOS) unless you have a special waiver (we’ll cover regulations later). In practice, many enterprise drones use radio controllers that can reach several kilometers. But on a corporate campus, range might be less of a constraint than line-of-sight and signal penetration. If your security office is in the middle of a building, thick walls could reduce control signal range. Many companies use extender antennas or mesh networks so that the drone can stay connected even at the far end of the property. Some advanced systems use cellular (4G/5G) connectivity, allowing a drone to be controlled over virtually unlimited range via the internet – but this may introduce latency and relies on cellular coverage. For most, a range of 1–2 miles is more than enough. It’s important to ensure video feed reliability at range; high-definition video can be bandwidth-heavy, so modern drones use adaptive streaming to keep a stable feed. Executives should know that even if a drone can physically fly 5 miles away, legal and practical considerations usually keep operations much closer (within say 0.5 mile radius for standard VLOS operations). Range can come into play if you have multiple facilities and want to centralize control – e.g., one control center managing drones at two sites a mile apart – which could be feasible with high-range systems or networked control. Ultimately, for corporate security, consistent coverage of your property is the aim, and range specs should comfortably exceed the furthest point you need to reach on your property (with line-of-sight maintained either by the pilot or observers).

- Speed and Agility: Security incidents often unfold quickly, so a drone’s speed can be a factor in how fast it can get on-site. Most multirotor drones fly at around 30–50 mph at top speed. This is sufficient for typical facilities; even a large campus a mile across can be traversed in a couple of minutes at those speeds. Fixed-wing drones, as mentioned, can be faster (60–100 mph), but the trade-off is they can’t stop quickly or hover. Multirotors can dart up and down, pivot in place, and even fly indoors (with proper stabilization sensors). Agility matters if you have a complex environment – lots of buildings, narrow alleyways, indoor-outdoor transitions (some drones can fly inside warehouses to check things then go back out). If you foresee needing to navigate in tight spots (say between refinery tanks or under structures), smaller and highly maneuverable drones might be favored. On the other hand, if your concern is covering a long perimeter quickly (say a fence around 500 acres), a fixed-wing or fast multirotor might be better to do a quick sweep. Also consider climb rate – how quickly a drone can gain altitude. If you have tall structures, you want a drone that can ascend rapidly to go over a building and check the other side when an alarm triggers there. Most quadcopters climb pretty fast (many >10 feet per second). This usually isn’t a limiting factor unless dealing with very tall installations (e.g., monitoring a skyscraper exterior – a niche case, albeit drones are used for building facade inspections, which is analogous to security in some urban settings).

- Weather Resilience: Real-world security operations face all weather conditions: heat, cold, rain, wind, perhaps snow or dust. Not all drones are equipped to handle inclement weather. Rain is a challenge because most small drones are not fully waterproof – electronics and motors can fail if water penetrates. However, there are ruggedized drones with weather resistance (IP-rated casings). Some industrial drones are IP43 or IP45 rated, meaning they can handle light rain or drizzle. A few high-end models boast IP55 or higher, capable of flying in moderate rain and dust. If your security needs must be met regardless of weather – for instance, critical infrastructure sites that cannot have downtime – you should invest in weatherized drones or protective measures (like only flying in rain if absolutely necessary, or using a protective coating). Wind is another big factor. Many drones can handle winds of 10–20 mph without much issue, using GPS and inertial stabilization to hold position. More powerful multirotors and especially larger units can manage 25+ mph winds, though battery drain increases. Fixed-wing drones generally handle wind better in flight (they slice through wind like airplanes), but takeoff/landing in wind can be tricky. If your facility is in a coastal or open area with frequent strong winds, choose a drone with a high wind tolerance spec (often listed as max sustainable wind speed). Temperature affects battery efficiency: very cold temperatures (<0°C/32°F) can reduce battery performance, sometimes by 15-25%. Drones may have battery warmers or you can keep spares warmed in a vehicle before flight. Very hot temperatures can also stress batteries and electronics – ensure the drone’s operating range covers your climate (e.g., up to 40°C/104°F or higher if in a desert environment). Night operations technically are not a weather issue but an environmental one – ensuring your platform has the necessary lights (for FAA anti-collision requirements) and sensors for dark flying (like altimeters or LiDAR for ground sensing) is important if you plan a lot of night sorties. Many enterprise drones now come with all-weather capability because professional users demand it.

- Reliability and Redundancy: Performance isn’t only about how high or fast, but also how reliably a drone performs its mission. Enterprise drones often include redundant components – dual GPS receivers, backup power systems to safely land if the main battery fails, collision avoidance sensors to prevent crashes, and self-diagnostic systems. For example, DJI’s professional drones have multiple IMUs (inertial measurement units) and compasses; if one fails or gives odd readings, the other takes over to keep flight stable. Some even have parachute systems as a fail-safe. When evaluating drones, see if the model has any fault-tolerance features – these add to operational safety which is paramount in corporate environments (you do not want a drone falling out of the sky onto a person or facility asset). Even though such failures are rare, planning for them is part of responsible program management. Regular maintenance (covered next) also ties into ensuring reliability; a well-maintained drone is less likely to have in-flight issues.

Maintenance and Operational Considerations for Security Teams

Deploying drones is not a one-and-done purchase; it introduces ongoing operational responsibilities. Security Directors and Operations Managers need to plan for the maintenance and day-to-day management of the drone fleet to ensure consistent performance and safety. Here are key considerations:

- Routine Maintenance: Just like any vehicle or piece of equipment, drones require regular check-ups. This includes:

- Pre-flight and Post-flight Inspections: Every flight should be preceded by a brief check of the drone’s airframe (no cracks or loose parts), propellers (no chips or warping), battery level and health, sensor functionality, and firmware status. After flight, especially after longer missions, inspect for any debris or wear (e.g., propellers may accumulate bug strikes or dust, which should be cleaned).

- Battery Care: Batteries are a critical component. They should be kept in recommended temperature ranges, not stored fully charged for long periods (most manufacturers suggest storing LiPo batteries at ~50% charge if not used for more than a few days), and cycled (used and recharged) regularly to maintain health. It’s wise to track battery cycles – many smart batteries do this internally – and replace batteries after a certain number of cycles or if capacity significantly degrades. Some companies adopt a practice of labeling batteries and rotating them to ensure even usage. Also, periodic calibration of battery gauges and firmware updates for smart batteries can ensure accurate readings.

- Propeller Replacement: Props can develop micro-fractures or deform over time, which might not be visible but can affect performance. It’s often recommended to replace propellers after a set amount of flight hours or if any incident occurred (like a minor collision or hard landing). They are relatively inexpensive, so erring on the side of caution is fine. Always keep spare propellers on hand.

- Motor and Gimbal Servicing: Brushless motors in drones are robust, but dirt or moisture ingress can cause issues. Listen for any odd sounds (grinding, clicking) which might indicate a motor needs cleaning or replacement. Gimbal assemblies (that stabilize cameras) have delicate parts; ensure they remain responsive and calibrated. Most systems have calibration procedures (either automatic or manual via software) – do this if you see horizon tilt in videos or jitter. Some organizations schedule professional servicing of drones annually or biannually, where the unit is sent to the manufacturer or an authorized shop for a thorough check. This can extend the life of the drone and catch issues early.

- Firmware Updates: Manufacturers periodically release firmware updates that improve stability, add features, or patch bugs (even security vulnerabilities). Assign someone to monitor these releases and apply updates during planned downtime. However, don’t update right before a critical operation – test the new firmware first, as occasionally updates can change behaviors or settings unexpectedly. Keep not just the drone updated, but also controllers, batteries, and any software in the ecosystem (like the base station or tablet app).

- Operational Readiness: Drones should be kept in a state of readiness so that they can be deployed at a moment’s notice for security incidents.

- Charging Regimen: Maintain a rotation such that a fully charged battery is always available for each drone. If using drone-in-a-box stations, they often manage charging automatically (keeping the drone charged and ready). For manual operations, some teams use multi-battery charging hubs. A best practice is to charge batteries after use but not leave them sitting full for too long (to avoid capacity loss) – smart charging cabinets that keep batteries at optimal charge until needed are an emerging solution. One can also implement a daily or weekly routine: for instance, every evening ensure all batteries are at least at 80%, so overnight incidents can be handled; top them to 100% in the morning if a daytime intensive operation is expected.

- Storage and Transport: If drones need to be moved between sites or deployed from a vehicle, invest in sturdy cases. Drones and their equipment should be protected from dust and shock when not in use. A cracked camera lens because a drone slid off a table is an avoidable operational hiccup. Having a proper storage area or charging room at the facility is beneficial – somewhere secure (to prevent theft of the drone itself), climate-controlled, and organized with all the gear.

- Documentation and Logs: It’s important to log flights and maintenance for both compliance and performance tracking. Note flight dates/times, pilot, purpose, and any anomalies or incidents (like if the drone had a GPS signal loss or required a sudden return). Also log battery cycles, replacements, and repairs done. These records help in scheduling maintenance and can be vital in investigating any security or safety incidents (for example, if there were ever a crash, you have records to show proper maintenance and pilot training, which could be important for insurance or regulatory scrutiny).

- Training and Proficiency: A well-maintained drone is only as good as its operator. Ensuring your security staff or dedicated drone pilots are well-trained is an operational must. This includes:

- Initial Certification: In the U.S., any commercial use of drones (which includes corporate security) requires FAA Part 107 certified remote pilots. Ensure all operators obtain this certification (FAA Drone Regulations for Commercial Drone Use: Guide to New Drone Laws and Part 107 FAA Drone Rules | DARTdrones UAV Pilot Training). The training for Part 107 covers airspace rules, weather, drone regulations, and safety – essential knowledge for safe operations.

- Regular Practice: Pilots should fly regularly to maintain their skills. Just like a perishable skill, if a security officer doesn’t use the drone for months and then needs to respond under pressure, their handling may be rusty. Building drone flights into the routine (daily or weekly patrols, even if just for practice or minor tasks) keeps pilots sharp. It also allows them to practice advanced maneuvers or response scenarios so that when a real event happens, they’re ready.

- Scenario Drills: Incorporate drones into security drills. For instance, run a simulation of an intruder breaching the fence: have the drone team respond as they would in reality, coordinate with ground security, track the “intruder,” and see how well information is communicated. These drills will help iron out protocols (e.g., how the drone pilot hands off info to the guard team, what the guard does if the drone loses sight, etc.). It will also boost confidence in the system’s effectiveness or highlight areas for improvement.

- Cross-Training: It might be wise to cross-train multiple personnel on basic drone operation, even if only one or two are primary pilots. In an emergency, you don’t want capability limited to a single person. Operations managers can ensure at least all shift supervisors know how to launch a drone and take over in an emergency if the primary pilot is unavailable.

- Integration with Security Team Workflow: Drones should become a seamless part of the security ecosystem, not a standalone novelty. Operationally, this means:

- Establish clear SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures) for when and how drones are to be used. For example, “If perimeter alarm triggers and drone is available, deploy drone before sending patrol officer, unless human response is immediately required for safety.” Or “Drone shall conduct a full perimeter sweep at the start of each shift and report any irregularities.” By formalizing these, you ensure consistent usage and maximum benefit. (We will talk more about developing SOPs in the implementation section, but from a tech perspective, your SOPs will also cover maintenance tasks like pre-flight checklists and fail-safe procedures).

- Communication protocols: How does the drone operator communicate with other security team members? Typically via radio – ensure the pilot has access to the security radio channel or a dedicated line to the SOC (Security Operations Center). The pilot might also need to communicate with external entities (like local law enforcement or, in some cases, air traffic control if operating near airports with prior approval). Having pre-established contacts and scripts for those communications is valuable. For example, if the facility is near an airport and you have an agreement to notify the tower when the drone is airborne, that should be in the checklist.

- Data management: Operationally, decide what happens to the video footage and data the drones collect. Is someone monitoring live video at all times (perhaps in the SOC)? Are recordings stored, and for how long? A common practice is to treat drone video like CCTV video – recorded and retained for X days unless needed for an investigation. Ensure you have the storage infrastructure if you plan to keep high-resolution recordings (it can accumulate quickly – hours of 4K video take a lot of disk space). There are video management systems (VMS) that can ingest drone feeds along with fixed cameras; integrating into those may streamline data handling. Also consider if the data needs to be encrypted or access-controlled to prevent unauthorized viewing – drones could capture sensitive views (like into private areas), so only authorized staff should be able to access the feeds and archives.

- Contingency Planning: Murphy’s law applies – batteries die, weather turns foul, or a drone might have a fault at a critical time. Operational planning means having backup measures:

- If Drone A is down for maintenance, do you have Drone B ready? Many programs start with at least two drones for redundancy.

- If weather prevents flying (e.g., thunderstorm), ensure traditional security measures are ready to fill the gap (maybe schedule an extra guard patrol in heavy fog since drones can’t fly safely).

- If a drone malfunctions mid-mission, have a procedure: Most drones have an auto “Return-to-Home” on low battery or loss of signal – configure that home point properly (usually the launch point or a safe landing area) and train pilots on using emergency modes. If a drone is about to crash or drift, do they know how to safely cut power or regain control? This comes from training but should be emphasized in SOPs.

- Also, consider insurance and liability: As part of operations, ensure your company insurance covers drone operations (often it can be added as a rider or separate policy for aviation liability). Have a plan for incident response if a drone accident occurs (e.g., secure the area, recover pieces, report to the FAA if required – serious accidents must be reported per Part 107 rules).

- Lifecycle and Upgrades: Operational planning includes the lifecycle of equipment. Drones are tech gadgets at heart and can become obsolete or less effective as new models with better features come out. A wise approach is to budget for periodic upgrades or expansions. For instance, plan that drone airframes might be replaced or significantly upgraded every 3-5 years to keep up with improvements (like longer battery life or better sensors). This prevents being caught off-guard when manufacturer support ends or when your drones no longer meet the demands (maybe you need more advanced detection that new drones provide). Keeping an eye on industry developments (which we cover in the Future section) will help plan these upgrades. It’s also a reason to maintain good relationships with vendors or integrators – they can alert you to useful upgrades or trade-in programs.

- Security of the Drones (Cyber and Physical): This is sometimes overlooked: drones themselves are part of your security infrastructure and must be secured. Physically, store them in a locked area to prevent tampering or theft. Digitally, protect the control systems – use encrypted links if available, change default passwords on any software, and ensure that data links have encryption (many enterprise drones do). Be mindful that some drones, especially those connected to cloud services, might upload data – ensure compliance with your company’s cyber policies and consider network segmentation for drone controllers. Also, Remote ID (a new FAA requirement) means your drones will broadcast an ID that law enforcement can pick up; ensure you’ve complied and registered those as needed (more in regulations section). While not an operational “maintenance” in the traditional sense, cyber maintenance (keeping software updated, following best IT practices) is part of drone operations now.

In conclusion, maintaining drone technology in a corporate security setting requires procedural discipline and integration with existing security operations. The hardware is sophisticated but needs care; the team is capable but needs training and practice. With solid maintenance schedules, trained personnel, and integrated protocols, drones can be a reliable and effective part of the security apparatus, running like a well-oiled machine (or rather, a well-charged device). It’s often useful for Security Directors to create a maintenance and operations manual specific to their drone program, incorporating manufacturer guidance and their own SOPs – essentially, a handbook that ensures continuity even if staff changes. By treating drones with the same rigor as one would treat, say, a company fleet of vehicles or an important IT system, you ensure they’ll be ready to deliver critical surveillance intelligence whenever and wherever needed.

Core Applications & Sector-Specific Use Cases

Having explored the technology, we now turn to practical applications – what exactly can drones do in the field of corporate security, and how are they being used across different industries and scenarios? In this section, we detail the core use cases for drone surveillance, from routine perimeter patrols to rapid incident response. We’ll also present anonymized or hypothetical case studies that illustrate these use cases in action, demonstrating the tangible benefits achieved. Different sectors – such as logistics, critical infrastructure, retail, and campus environments – have unique security challenges; we will examine how drone solutions can be tailored to each. The goal is to translate capabilities into real-world operations and show Operations Managers how to deploy drones for maximum impact in their specific context. (Where possible, we’ll also note any lessons learned or operational insights that can help ensure these deployments run smoothly.)

Perimeter Patrol and Intrusion Detection

One of the most popular applications of security drones is perimeter surveillance. Virtually every facility – from warehouses and factories to corporate office parks – has a boundary that needs monitoring. Traditionally this might be done with fence sensors or periodic guard tours. Drones revolutionize perimeter security by providing frequent, mobile patrols that can cover the entire boundary quickly and detect anomalies in real time.

Use Case Example – “Eagle-Eye Perimeter Watch”: Consider a large distribution center of about 200 acres, surrounded by a chain-link fence. The site experienced occasional night-time fence breaches where thieves cut the fence to steal stored goods. The security team deployed a drone with an optical/thermal camera to fly along the fence line every hour at night. The drone’s thermal imaging could see if anyone was lurking outside the fence or if a section of fence was disturbed (the temperature difference of a fresh cut or a person’s handprints on metal can sometimes be seen). On one occasion, the drone’s operator noticed an unusual heat spot near the fence in a remote corner – zooming in, they saw two individuals hiding by the fence where they had just cut an opening. The operator immediately triggered the drone’s spotlight and loudspeaker, announcing that security forces were on their way. The suspects, startled and aware they’d been spotted, fled before stealing anything. Ground guards were dispatched to that fence segment and secured the cut. Result: an attempted theft was deterred without any loss, and repairs were made before dawn. Over several months, the mere knowledge that a drone patrols the fence regularly (signs were posted noting “Drone Surveillance in Use”) dramatically reduced fence-cut attempts. The ROI was clear as inventory losses dropped to near zero.

From this example, we see key benefits: early detection, deterrence, and rapid coverage. A drone can typically fly the entire perimeter of a facility in minutes. Modern drones can even do this autonomously on a programmed path, using GPS waypoints or following the fence line via machine vision. If integrated with intrusion sensors, the drone might not even have to patrol constantly – it could be automatically dispatched the moment a fence sensor triggers, potentially catching intruders in the act. Compared to a walking patrol that might take an hour to circuit the property (and might pass a given point right before intruders strike there), a drone can be on the scene far more responsively and persistently hover to monitor until backup arrives.

For critical infrastructure sites like power plants or data centers, perimeter drone patrols add a high level of assurance. Some companies use drones with thermal cameras specifically to spot anyone approaching the perimeter in darkness, because the thermal signature pops out against a cooler background (Navigating Modern Security Challenges: The Crucial Role of Physical and Surveillance Security Solutions – Cuneo Consulting). Drones can also cover perimeters that are hard to access on foot – for example, a facility with a waterfront boundary (drones can fly over water) or rugged terrain. If a site has an external perimeter and an internal one (say a secondary fence or building line), the drone can check both in one flight by doing concentric loops.

Operational insight: When using drones for routine patrols, vary the schedule or pattern if possible. Predictable patterns could theoretically be timed by savvy intruders. Drones give the ability to be unpredictable – use that advantage (e.g., sometimes do two back-to-back patrols, sometimes skip an hour, etc.) to keep adversaries guessing.

Asset Protection and Asset Tracking

Beyond just the perimeter, drones are very useful for watching over specific high-value assets or areas within a facility. This could mean monitoring an outdoor yard with expensive equipment, tracking the movement of sensitive materials, or keeping an eye on a remote warehouse on a property.

Use Case Example – “Overwatch for the Loading Yard”: A large manufacturing company has a secured yard where finished products on pallets are staged before shipping. These products are high-value, and there were incidents of tampering and theft in the past. The yard is too large to cover with static cameras everywhere (and moving goods sometimes block views). The company introduced a drone surveillance routine focused on this yard. Whenever a shipment is being prepared or moved, a drone takes off and hovers above the yard, providing a live overhead feed to the security operations center. This aerial perspective allows security to track the assets (pallets, containers, etc.) as they are moved by forklifts from storage to trucks. If any unauthorized activity occurs – e.g., a pallet being moved to an unusual location – the security team sees it immediately. In one scenario, the drone feed helped catch an operational issue: a driver attempted to leave with a truck before proper sign-off, which could have been theft or simply a mistake. The drone noticed the truck departing the loading bay without clearance and alerted security to stop it at the exit gate. It turned out to be a miscommunication, but it illustrated how constant eyes on assets prevent things from slipping through cracks. The workers in the yard also knew they were being observed, which improved compliance with protocols (like no leaving pallets unattended). Result: No more losses occurred from the yard, and inventory accountability improved. The overhead footage also proved useful for operational analysis – the logistics managers reviewed it to optimize the layout and flow of the yard.

This example shows drones acting as a roving CCTV, but with the flexibility to follow assets around. For companies with large outdoor storage (construction materials, vehicles, etc.), drones can do regular inventory sweeps, literally flying grid patterns over a laydown area to check that everything is in place. With machine learning, some systems can even automate counting or recognizing objects (for instance, matching what’s supposed to be there versus what the drone sees).

In sectors like logistics and trucking, one use case is to have a drone automatically track high-value shipments. Imagine a scenario: a truck carrying valuable microchips enters a big industrial campus. A drone could follow that truck from the gate to the loading dock, keeping an eye on it to ensure it isn’t intercepted or tampered with on the way. This might sound extreme, but in some environments (say large ports or multi-tenant industrial parks), it adds a layer of security for critical deliveries.

Another asset-related use is protecting company vehicles or machinery. For example, mining or energy companies with lots of equipment might use drones at night to ensure expensive machinery is not being disturbed. Drones can also check on remote assets like pipeline valves, solar panels, or telecom towers in a corporate network, blending security and maintenance inspection.

The key insight for asset protection is that drones provide on-demand visibility exactly where you need it, when you need it. They can bridge gaps between static cameras or go to places that are cost-prohibitive to wire with CCTV (like acres of materials or an open field parking lot). By actively tracking asset movement, they reduce reliance on after-the-fact audits – you have a real-time audit as things move.

Rapid Incident Response and Emergency Support

When an alarm goes off or an emergency happens on site, every second counts. Drones shine in incident response by being first on scene to assess and sometimes even intervene. We touched on this in earlier sections as a strength; here, let’s focus on specific scenarios and sector angles: